“My biggest fear is losing my memory because memory is what we are.”

“My biggest fear is losing my memory because memory is what we are.”

~Nick Cave, 20,000 Days on Earth

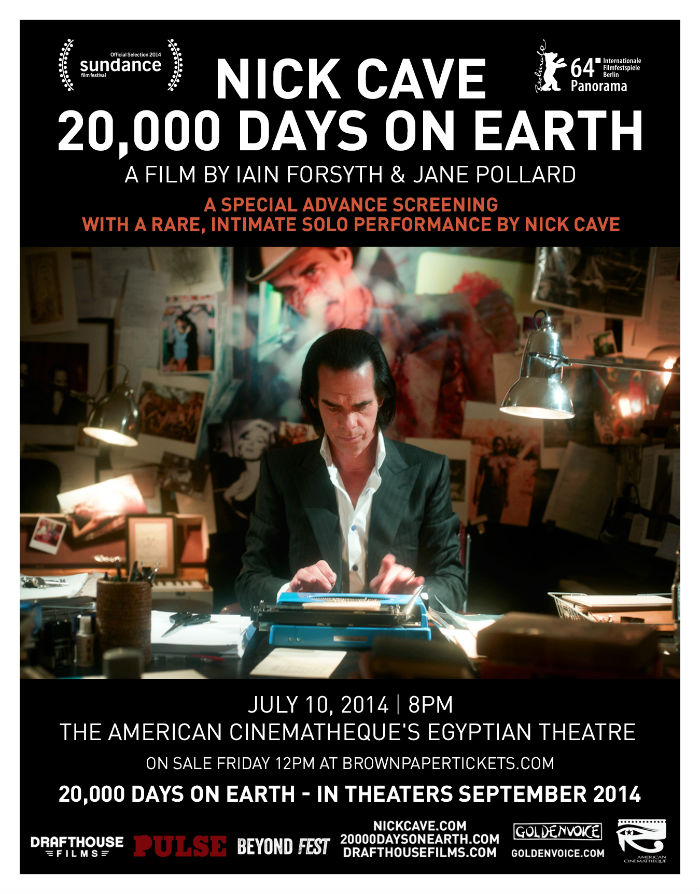

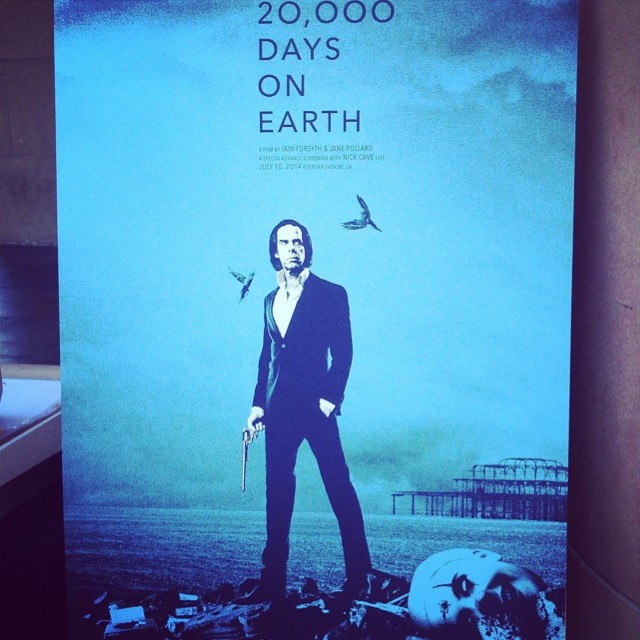

Within the first 60 seconds of 20,000 Days on Earth, we see a time lapse of the life of Nick Cave. But it’s not just a fast forward of home videos, it’s a mood real of the eras past and his candle-lit corner in it. Immediately, the air is sucked out of the room, and we are have entered the Cave.

They say the greatest artists are timeless, and my favorites are those that play with the idea of time, like puppetmasters tugging on the strings of a marionette. There are those that seem like they were transported from the past, like Jack White, and those that sound like they have come back from the future, like Trent Reznor. And then there’s Nick Cave, who sounds like he’s come from both, perhaps a land where time isn’t linear.

In the Q&A after the screening, Cave would explain that a lot of the documentary isn’t real, that it’s not the kind of rock doc that is trying to get at the man behind the image, because “there isn’t one.” Instead of “watching someone do the dishes”, we saw Cave waking up and getting out of bed, working in his office, in therapy, driving, in the studio, and on the stage. Intimate moments overlaid with narrative insight; taking place in sorta real, sorta not locations. It was his office, only slightly redecorated. He sat down with Warren Ellis to eat, only Ellis had not actually made the meal himself. It was a world tinkered with yet still authentic; it was a perfect reflection of his music.

Nick Cave is one of the best lyricists of our time, and the soul of the movie is about being a writer. He spoke about the notion of the counterpoint, explaining that songwriting is “like letting a child into the same room as a Mongolian psychopath or something.” It reminded me of hearing “Higgs Boson Blues” for the first time, and being snapped out of the dark painting he was creating when he uttered the words ‘Hannah Montana’, ‘Miley Cyrus’, and ‘Wikipedia’, in stark juxtaposition the mentions of Robert Johnson and Lucifer. In the movie, he explains to his therapist a habit of his junkie years: going to church before going to score. The balancing act.

My favorite part in the film reminded me of the way I felt when I saw It Might Get Loud, and Jimmy Page is air guitaring to Link Wray: we are presented with a moment of Warren Ellis and Cave sort of curled up together on the floor, Ellis’ eyes locked on his Korg and Caves fingers wrapped around a microphone. They’re working out a song, and Ellis’ shoes are tapping together, Cave’s all socks and skinny knees. It’s imperfect, child-like. But in that moment you get a glimpse of raw musicianship, and to me this was more soul-baring than seeing Cave washing the dishes. In fact, between moments like that and watching Cave watching Scarface with his twins while they share a slice of pizza, I realize that when he said that the movie isn’t real, he was kind of lying. And that’s exactly the grey, confusing area that embodies Cave’s work.

“That’s what me & Warren do… we do despair and dread. Luckily there’s a market out there for that sort of thing.” The Q&A, which should have had a moderator and some other method of organization as it became very awkward for both him and us, took place between Cave’s first solo U.S. show. Seated at a piano, we were treated to “Into My Arms”, “Love Letter”, “The Mercy Seat”, “The Ship Song”, “God is in the House”, and “People Ain’t No Good”. Many of these were requests, and they played out spectacularly. While I lamented the fact that they weren’t played all together to enable me to get fully engulfed in a mood, looking back, it made the night more unique.

And for the opportunists out there, we learned that Cave and Ellis really want to score a horror film, and as for his surplus music: “there are a bunch of lyrics floating around… what, have you got a band? I’ll sell them to you.” he told one audience member.

Though Cave confessed he doesn’t like nostalgia, his aforementioned fear of losing his memory seems to set an omnipresent battle within him. How does one justify where they’ve been and where they’re going? Perhaps this is fuel in the artist struggle, what sets them apart from the rest of those who are content with just being. And, as Cave admits 20,000 Days “cast more mystery over the whole thing”; viewers can expect to further be entangled in the web of Cave’s world after seeing this film.

Very well said Jamie. Thank you for putting to words such an intense and interesting evening. My mind is still buzzing with it. I cannot wait to see the film again— and I don’t think I will ever get over Nick Cave playing The Ship Song because I asked him to. Absolutely incredible evening. Glad I got to share it with you!

Thank you… it was a great night!